Puccini’s Turandot

Turandot is truly a masterful work and should be, I’d say, on the list of favorites of any opera fan. This piece, as well as any full opera, would be best suited for someone who is versed in classical and opera pretty well already. Otherwise, some of the slower scenes may get a little disinteresting, especially if the listener isn’t familiar with the libretto or the language in which it’s written.

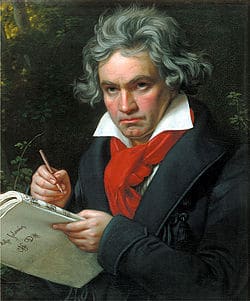

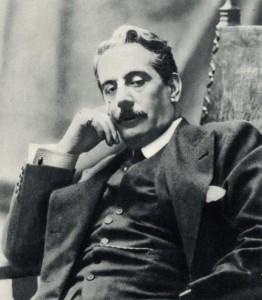

First, we’ll start off with the libretto itself. Written, in Italian, by Giuseppe Adami and Renato Simoni, the storyline of Turandot comes originally from The Book of One Thousand and One Days, a Persian collection of stories, where the character Turandot (meaning “daughter of Turan”), a cold-hearted Turkish princess can be found. Surely the story has been the inspiration for many works, but most notably it was adapted as a play in 1762 by Carlo Gozzi, and then published in 1802 by the German writer and poet Friedrich Schiller. Turandot arose yet again in operatic form in 1917 and again in German, but by Italian composer, writer, and teacher Ferruccio Busoni (Busoni wrote his own libretto based on Gozzi’s play). Puccini began working on Turandot in March of 1920, after meeting with the original librettists (Adami and Simoni), and he began actual composition of the music in January of 1921. By March of 1924 he had reached the final duet of the work, but was displeased with the text being used and did not continue until October 8th, deciding to use Adami’s 4th version of the text. Two days later he was diagnosed with throat cancer and on the 24th of November he went to Brussels, Belgium to seek experimental radiation treatment for his condition. He died on the 29th of November, leaving Turandot incomplete, later to be finished by Italian composer and pianist Franco Alfano. The ending chosen by Alfano has been up for debate for years, and the debate remains open today. Turandot premiered in Milan at the Teatro alla Scala on the 25th of April, 1926 without Alfano’s ending, conducted by the great Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini. The first performance of the opera with Alfano’s ending was conducted by Argentinean conductor and composer Ettore Panizza.

Turandot takes place in Peking, China during legendary times. The story opens in front of the imperial palace, where a Mandarin announces, “Any man who desires to wed Turandot must first answer her three riddles. If he fails, he will be beheaded.” A commotion begins over the Prince of Persia having failed, and being sentenced to beheading at moonrise. The crowd rushes towards the palace gates and is repelled violently by the guards. During this clamor an old blind man is knocked to the ground. The man’s slave-girl, Liù, calls for help, being answered by a young man who recognizes the old man as his long lost father, Timur, the deposed king of Tartary. The young Prince is excited to see his father again, but fears that should he say his name that it may incite the rage of the Chinese rulers, having conquered Tartary. Timur tells his son that of all his servants Liù is the only one who remained loyal to him. When asked why by the Prince, Liù says that it is because once, a long time ago in the palace, the kind smiled upon her. As the moonrise becomes nigh the commotion of the crowd dies down into silence as the Prince of Persia is led out to be executed. The crowd finds the Prince of Persia so handsome that they beg Princess Turandot to spare his life. Turandot appears, but with a single uncaring gesture she orders the execution to go on as planned. When the Prince of Tartary sees Turandot he is so captivated by her beauty that he instantly falls in love with her. He joyfully calls her name three times, and as he says her name the final time the Prince of Persia echoes and the crowd screams in horror as he is beheaded. The Prince of Tartary is so dazzled by Turandot that he rushes to proclaim his intention to marry her by striking the gong in front of the palace three times (the symbolic gesture of would-be suitors) when he is stopped by the three ministers, Ping (the Lord Chancellor), Pang (the Majordomo), and Pong (the head chief of the Imperial Kitchen). The ministers try to cynically dissuade the Prince, telling him to save his own head and return home. His father Timur urges him not to take the risk and Liù, secretly being in love with him, begs him not to attempt Turandot’s riddles. The Prince is touched by Liù’s words and, telling her not to cry, he asks her to make exile more bearable for his father and to never leave him should he (the Prince) fail to answer the riddles correctly. Ping, Pang, and Pong try one final time to stop the Prince, but he ignores their words. The Prince of Tartary calls out Turandot’s name three times and each time Timur, Liù, and the ministers reply, “Death!”, and the crowd gasps. The Prince rushes towards the gong and strikes it three times, declaring himself a suitor. Turandot emerges from the palace and from the balcony accepts the Prince’s challenge as the ministers laugh sardonically at his foolishness. Thus ends the first act.

Scene one of act two opens before sunrise in a pavilion at the imperial palace. The ministers Ping, Pang, and Pong are preparing for either a wedding or a funeral and begin to lament their positions. They grow weary of constant laboring over palace documents and presiding over endless rituals. During this Ping beings to reminisce about his home in Honan by a small lake surrounded by bamboo. Pong misses his home in the forests near Tsiang, and Pang talks of his gardens near Kiu. The ministers share memories of their lives away from the palace but come back into realization of their positions and Turandot’s reign filled with clamor and bloodshed. They also grow tired of having to accompany young men to their deaths and having to recall their fates.. But as the palace trumpets sound the ministers prepare for the Emperor’s arrival and the trial of the young Prince.

Scene two of act two opens in the courtyard of the palace at sunrise with the Emperor Altoum, father of Turandot, sitting on his thrown. The Emperor urges the Prince to back out while he still can, but the Prince refuses. Turandot enters and explains that she descends from the Princess Lo-u-Ling, who reigned “in silence and joy, resisting the harsh domination of men” until she was raped and killed by the prince of an invading kingdom. Turandot claims that Lo-u-Ling is living again through her and that her reason for her trials of suitors is to never let a man possess her to avenge her ancestress. After refusing Turandot’s final suggestion that he desist, the Princess presents the Prince with her first riddle, “What is born each night and dies each dawn?” The Prince answers correctly, “Hope.” The Princess presents her second riddle, unnerved, “What flickers red and warm like a flame, but is not fire?” The Prince thinks for a moment and replies, “Blood.” Turandot is surprised at his second correct answer. The crowd cheers for the young Prince, only angering Turandot. The Princess presents her third and final riddle, “What is like ice, but burns like fire?” The Prince thinks as Turandot scorns him, but despite her sneering he decides confidently on his answer and proclaims, “Turandot!” Turandot throws herself at her father’s feet as the crowd cheers, begging him not to leave her to the Prince, but the Emperor insists that she must keep her word. Turandot cries out in disdain but the Prince stops her and offers her proposition, he proposes, “You do not know my name. Bring me my name before sunrise, and at sunrise, I will die.” Turandot accepts, and her father confesses his hope that he may call the Prince his son one day. The curtain falls on act two.

Scene one of act three opens at night in the palace gardens with the sounds of heralds calling out, “This night, none shall sleep in Peking! The penalty for all will be death if the Prince’s name is not discovered by morning!” The Prince waits the morning and his victory, proclaiming, “Nobody shall sleep! Nobody shall sleep! Not even you, O Princess!” This is the well-known aria, “Nessun Dorma”. The ministers Ping, Pang, and Pong go to the Prince, offering him riches and women if he would only give up his quest for Turandot’s hand, but he, once again, refuses to let her go. Having seen Timur and Liù talking with the Prince and assuming they must know his name, a group of soldiers drag them in to him. The Prince feigns ignorance of who they are.. Turandot then enters, ordering Liù to give up the Prince’s name. She says that she alone knows his name, but that she will never reveal it. Ping, unable to convince her to give up the name, sentences Liù to be tortured. Turandot, moved by Liù’s resolve, asks her who put so much strength in her heart. Liù replies, “Princess, Love!” Turandot orders Ping to keep torturing her until she gives in, but Liù counters Turandot, telling the Princess that she, who is “begirdled by ice”, shall one day know love as well. Liù gathers what life she has left, lunges for a nearby soldier, takes his dagger from his belt, and stabs herself. She falters over in the direction of the Prince as the crowd yells for her to reveal his name, but falls dead without giving in. Not fully aware of Liù’s fate, due to his blindness, Timur is told what just happened, bursting into cries of anguish. He warns that the gods will be offended by this outrage, shaming and frightening the crowd. Liù’s body is taken away and in procession the crowd and a grieving Timur follow. Alone with Turandot, the Prince scorns the “Princess of death” for her cruel actions, but approaches her, taking her in his arms, and despite her attempts to stop him, kisses her.

(At this point Puccini left the work incomplete. The remainder of Turandot from here on was finished by Alfano, and is included in the version of the opera being reviewed.)

The Prince of Tartary endeavors to bring Turandot to reciprocate his love, at first disgusting her. The Princess initially denies him, but following his embrace she begins to feel herself giving in to feelings of love. She requests that he simply leave, without asking for anything more, and take the mystery of his true identity with him. The Prince, instead, finally reveals his name, “Calàf, son of Timur”, then handing his life over to the Princess, giving her the power to end it.

The curtain rises on scene two of act three at sunrise in the palace courtyard. Calàf and Turandot go before the Emperor’s throne and the Princess declares that she knows the Prince’s name. The Emperor and the crowd listen anticipantly as she says, “It is… love!” With that the crowd cheers the two lovers in acclamation in the closing chorus, “O sole! Vita! Eternità!”

Puccini’s Turandot is a thoroughly moving piece, with rousing themes and tonal references. It has a unique sound and is regarded to be one of the composer’s most colorful operas. The critical response to Turandot has been mixed, it having been called a flawed masterpiece at best. Reviews include opinions in the resoundingly negative and the supportive, touching on the criticism that the work didn’t do justice to the characters and the credit to the composer that the final declaration of love by Turandot cannot be determined by the original text to be any more than “hormonal”. It is also said that Calàf’s obsession with the Princess cannot be proven to be anything more than merely physical. I admit that the final scene of act three is a bit presumptuous, and may be a shot in the dark at bringing the work to a close. However, being a composer and not just a critic, I understand the difficulty of finishing another’s work and also the difficulty of ending such a powerful story. Therefore, I believe this to be a wonderful piece of music and I would recommend it to anyone who is a fan of opera and who has not yet seen or heard it. If you’re a newcomer to Turandot you may just find it to be your favorite after your first hearing.

Puccini’s Turandot is a thoroughly moving piece, with rousing themes and tonal references. It has a unique sound and is regarded to be one of the composer’s most colorful operas. The critical response to Turandot has been mixed, it having been called a flawed masterpiece at best. Reviews include opinions in the resoundingly negative and the supportive, touching on the criticism that the work didn’t do justice to the characters and the credit to the composer that the final declaration of love by Turandot cannot be determined by the original text to be any more than “hormonal”. It is also said that Calàf’s obsession with the Princess cannot be proven to be anything more than merely physical. I admit that the final scene of act three is a bit presumptuous, and may be a shot in the dark at bringing the work to a close. However, being a composer and not just a critic, I understand the difficulty of finishing another’s work and also the difficulty of ending such a powerful story. Therefore, I believe this to be a wonderful piece of music and I would recommend it to anyone who is a fan of opera and who has not yet seen or heard it. If you’re a newcomer to Turandot you may just find it to be your favorite after your first hearing.